The Passover Haggadah (Haggadot, in plural) is a fundamental text in the long history of Jewish religious and cultural life. As such, it is the most published work of all Jewish books ever since it was extracted from the established Jewish prayer book in the 13th century. While the source texts are in Hebrew and Aramaic, both Semitic languages that are read from right to left, the Haggadah has thousands of known versions, published in many languages and places around the world. This compact book accompanies the Passover Seder festive meal that celebrates the biblical exodus from Egypt by fulfilling the command in the Book of Exodus 13:8: “And you are to tell your child on that day, saying: ‘It is because of what God did for me, when I went out of Egypt.’”

The responsibility to tell the liberation story to one’s child(ren) is performed through the Haggadah’s fourteen sections, of which the meal itself is one of the concluding sections. Most of the Passover Seder night is spent in communal reading and singing, and in sampling food items that symbolize the harshness of slavery or the ceremonial sacrifices made in the Temple before it was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE. While the Haggadah is a ritualistic text, it is also a practical handbook used at the dining table. Therefore, it is not uncommon to find Haggadot that have food and wine stains in them—a sign that they have been put to a good use!

The ASU Library collection of Haggadot includes facsimiles of well-known illuminated manuscripts, such as the Sarajevo Haggadah that was created in Spain in 1350 but is named after Sarajevo, its location since 1894, where it is held by the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This Haggadah survived the Holocaust thanks to both the museum director and curator Derviš Korkut, both of whom risked their lives by hiding this manuscript in a mosque until the end of the World War II. During the Siege of Sarajevo, which lasted from 1992 to 1996, the museum was damaged by shelling, but the Haggadah came to no harm. Its illustrations depict both contemporary Passover customs and also Torah stories, and its text additionally includes a prayer book and Jewish liturgical poems by celebrated Hebrew poets of Spain’s Islamic golden era (SPEC D-4799). Other facsimiles in our collection include the Kaufmann Haggadah (Spain, c.1350–1360; SPEC D-1405), the Von Geldern Haggadah (1723; SPEC C-2276), and the sizeable Rothschild miscellany from Northern Italy––a lavishly illuminated manuscript that encompasses 37 different works, including a Haggadah (1479; SPEC D-4295).

While the earliest preserved text of the Haggadah is recorded in the 9th century prayer book of Rabbi Amram Gaon, the first surviving printed Haggadah is a 1480 incunabulum from Guadalajara in Iberia. The earliest printed Haggadah in the ASU Library collection (SPEC PAM-3915) is a 1892 Hasidic edition published in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, which was a major Jewish cultural center before the Holocaust. Like other print Haggadot in our collection, this item used to be popular and affordable but is now difficult to obtain. It features fifteen different commentary sources, including miracle stories by Moshe of Dzialoszyn in Poland, and its seven illustrations are based on the 17th century Amsterdam Haggadah. The earliest American Haggadah in the ASU collection, published in New York in 1912 (BM674.648 .H4 1912), boasts its inclusion of 60 commentaries, Halakhot (Jewish laws), and miracle stories. Since the secondary texts were published only in Yiddish, this Haggadah version clearly catered to readers who arrived in America as part of mass immigration from Eastern Europe and who were neither scholars of Hebrew nor fluent in English yet. This Haggadah also includes readings from the biblical book of Song of Songs, a custom that was first recorded in the Tractate Soferim (8th century).

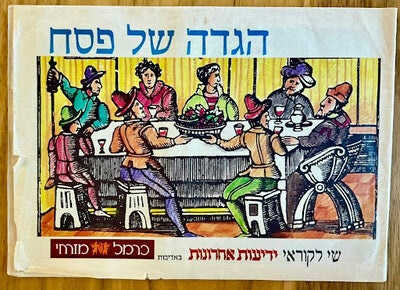

Print Jewish newspapers used to distribute free Haggadot with the holiday issue, sometimes by collaborating with sponsors, such as organizations supporting religious causes or corporations selling coffee or wine. These are represented in our collection by items such as the iconic Maxwell House Haggadah in its deluxe 1965 edition (BM674.643 .H35 1965) or by a 1967 Haggadah distributed by the Davar newspaper in Israel. The latter, sponsored by the Friedman-Tenuvah Winery and produced by the Victor Arnon graphic studio, not only features an unusual elongated format and a distinct cover in a mid-century style, but also includes a preface by the Kabbalist Rabbi Zvi Brendwien (B674.6 A3 1967). Another example of a free newspaper Haggadah, sponsored by the Karmel Mizraḥi Winery, was published by the popular Yediʻot Aḥaronot (Latest News) newspaper, in 1989. Its illustrations were copied from the Livorno Haggadah (Italy, 1885) and the New York Haggadah (1920) and its wide format (21 x 29 cm) was probably easier to use at a crowded dining table (SPEC PXL-474).

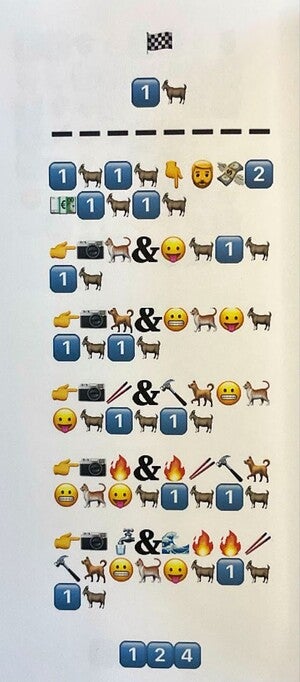

In addition to Haggadot, the ASU Library collection includes items inspired by the multilayered text of the Haggadah. An artist’s book (a form of art in a book shape) made by former ASU student Michelle Segal focuses on the Ḥad Gadya text (One Kid, or little goat). This accumulative children’s song was added to the Haggadah together with another accumulative song, “Who Knows One?,” in a 1590 version of the Prague Haggadah. As the first children’s song recorded in print, the Ḥad Gadya song is pretty grim, describing a goat eaten by a cat, which is bitten by a dog, which is bitten by a stick… it goes on until the Creator slaughters the Angel of Death. These two songs conclude the Haggadah. Segal’s bilingual (Hebrew-English) work from 2007 plays with the cumulative aspect of the song (SPEC C-3376).

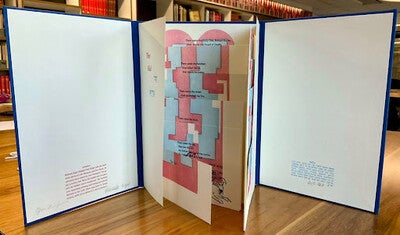

Another movable (pop-up) book in our collection, created by Keith Moseley and Linda Birkinshaw in 2006 (SPEC C-3689), is based on the the Birds’ Head Haggadah from the south of Germany—-the earliest known complete manuscript of an illuminated Haggadah (1300). It is so dubbed because the heads of all the Jewish figures are replaced with birds’ heads. Scholars still debate the meaning of this: some believe it represents the Jewish prohibition on figurative art, which was just lifted at the time, while others see it as a reference to the Israelites fleeing Egypt (Deuteronomy 32:11), or the artist’s loyalty to the German Kaiser at the time, symbolized in an eagle head, or as more evidence to Antisemitic dehumanizing of the Jews.

Lastly, Martin Bodek’s 2018 Emoji Haggadah (BM695 .P35 H35 2018) exclusively uses emojis to illustrate the traditional text. While probably not meant for being read out loud, this take on the Haggadah is certainly entertaining.

Several new Haggadot are published every year and today, people may even use websites such as Haggadot.com or Sefaria.org to customize their own Haggadot. We hope that this essay will encourage you to explore the ASU Library collection of Haggadot, including the rare ones. Happy Passover!

- Rachel Leket-Mor, Open Stack Collections Curator